„Expect the unexpected and rebound if you sometimes fall.“

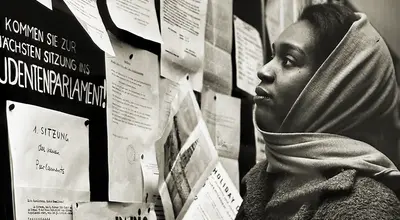

Welcome to insights from the 2023 International Dialogue on Education (ID-E) Conference. Held at the Embassy of Canada, the conference sought to articulate the multifaceted concept of innovation in higher education, drawing perspectives from Canada, the United States, Scotland, and Germany. Each country and its distinguished panel representatives considered the panel’s central question — what does a culture of innovation on campus look like — in vastly different ways.

For the United States, Dr. Jeff Zimmerman, Director of the Organizational Leadership Program at Northern Kentucky University and a Fulbright Scholar, provided a unique perspective. He discussed his innovative approach to fostering a culture of innovation on U.S. campuses, emphasizing a consumerist lens in viewing students as 'customers' and focusing on providing them with the tools to succeed in a complex global marketplace.

Read this exclusive interview and acquaint yourself with the remarkable Dr. Jeff Zimmerman and gain insights into his innovative educational philosophy. Join us, as he shares his perspectives into the topic of “Educating for Innovation” and most importantly, as he sheds light on his life and experiences as a Fulbright scholar.

During the ID-E Event "Exploring Differences: Education for Innovation", you shared your insights on various aspects of the topic. Is there anything specific that you would like to talk about or elaborate on, which perhaps didn't receive as much attention during the panel or discussion?

Thank you so much for asking. One challenge of innovation is that it requires us to convince others to spend their money, knowledge, equipment, human capital, and time – all of which are fixed, short-term costs – for a long-term outcome that is not guaranteed. In other words, no one can guarantee that an innovative change made today will equate to a desired future outcome.

When viewed in this way, innovation may become less appealing to some as it involves a risk (i.e. invest my money, knowledge, equipment, or time today for a non-guaranteed future outcome). However, NOT innovating today incurs the risk that we could be left behind by others who do attempt to innovate today.

In my experience and research, I have come to believe that, in many cases, the risk of not innovating (enough) in the present leads to more negative outcomes than the risk of innovating. So, when it comes to educating for innovation, I believe that it is very important to make our students aware of the fact that innovation itself can be scary – particularly when we are first exposed to a new or controversial idea that runs counter to everything we may have known or experienced. Furthermore, just because one may be inclined to automatically write off a new or controversial idea as “dumb or stupid” simply because it is different does not mean that we should do this.

In fact, what I have found helpful in terms of preparing my students to capitalize on innovation, is simply making them aware of how easy it is for all of us – myself included – to fall victim to implicit bias. Knowing how and why we can become biased towards new ideas, products, processes, or protocols is the first step in overcoming such bias, which allows us to become more receptive to the innovative and ground-breaking ideas that are needed in a constantly changing global marketplace.

Can you share a bit about your journey in becoming a Fulbright Scholar? What drove you to apply for the Fulbright scholarship? Additionally, what were some of your notable experiences during your time at the University of Pécs in Hungary? How will these experiences affect your academic (and personal) life back in the USA?

I have known about the Fulbright Scholar Program through friends and acquaintances who had also served as Fulbright Scholars in various countries over the years. Nevertheless, I knew how challenging the application process was and after about a year of brainstorming potential proposal topics, I finally decided to take the leap and apply. I worked so hard on my first application, and even though I ended up being listed as an alternate, I was happy with making it past the first round on my first application. I had friends who were full professors at their respective institutions who never made it past the first found until almost a dozen attempts. I then took the lessons learned from my first application and enhanced my application in my second attempt, which ultimately proved successful.

One of the main reasons I applied was that I simply wanted to continue expanding my teaching and research in a cross-cultural context. I love the interplay of teaching and research and the Fulbright Scholar Program was a good fit – especially for my deep interest in cross-cultural leadership (one of my research areas). Finally, having completed my MBA and PhD at the University of Klagenfurt (Austria) more than a decade earlier, I believed the Fulbright Program would allow me another opportunity to learn from (and give back to) a European university.

Some of the most notable experiences at the University of Pécs (Hungary) was how international the programs were in which I was teaching (undergraduate and graduate levels). I was simply amazed at the extensive diversity of the students whom I was teaching (and my home institution – Northern Kentucky University – is a pretty diverse place). I literally had classes where 85% of the students were not from the EU. In one of my classes with around 30 students, there were 20+ nationalities represented (only four of which were from the EU).

Furthermore, I really appreciated what I would call a more “active learning” approach that I often found in my Hungarian classes. For example, just as I had experienced two decades prior in my graduate work at the University of Klagenfurt, most of the faculty with whom I interacted teaching graduate and/or undergraduate seminar courses at the University of Pécs Faculty of Business and Economics would engage students with a formidable semester-long project that was supplemented with on-going lecture. The challenge for many students was that an initial look at the project would make many think the instructor was simply a little crazy with unrealistic and impossible expectations (i.e. requiring undergraduate students to come up with a full-fledged human resource plan to open up a new facility led by an expatriate in third-party country). Nevertheless, that initial perception would fade over time to a more accurate reality that, yes, indeed, students could come up with some very well thought out and comprehensive plans. This is one type of practice that I will be incorporating into my upcoming courses when I return to the USA.

As I took my family (wife and two young children) with me, the openness of the community was so important for our family as we adjusted to our new home in Pécs. I am grateful to everyone at the University of Pécs who may not have realized just how much of a support they really were to us (from the university international office, to work colleagues – especially Zsofi, Brigi, Andras, Akos, and Petr – all the way down to the security guard outside the business school who always had an answer for my questions). Just as important was the insight and support we received from the friends we made at our children’s school. The many car and bus rides we shared with them led to so many fruitful conversations and lasting relationships. All of these experiences highlight the importance of not judging a book by its cover. For example, just because we spoke a different mother tongue than many of those whom we met, does not mean we did not share commonality in the challenges and issues we faced. Similar to the idea that innovation can be a scary proposition, just because someone may be different from us does not mean that they cannot add to the value of our collective existence.

Balancing the roles of Associate Professor and Director of the Organizational Leadership Program at Northern Kentucky University is already a significant responsibility. Could you share insights into how you managed this balance, particularly during the semester you spent abroad? What were the challenges you faced, and what expectations did you have for yourself in fulfilling both roles?

The Organizational Leadership Program is a pretty large program (i.e. 7+ faculty members, teaching 35+ courses a semester to more than 1,000 students). Actually, I was fortunate in that I was able to take a sabbatical during the semester, which allowed me to focus on my Fulbright Scholar work. This allowed me to have more realistic and healthy expectations for my Fulbright experience.

Additionally, the only way I could step away for a semester was because I have excellent (selfless & motivated) colleagues at NKU who have my back even when I am away. This is nowhere more true than the Coordinator of the OL Program (with whom I have worked in administering the program over the last 7 years). This meant that leading up to my semester abroad, I had weekly meetings with the Coordinator to figure out how we could split the workload among others. There were, of course, some issues that I still had to manage from abroad and this meant a few virtual meetings or emails that ultimately had to take place. Nevertheless, being 6 hours ahead of East Coast Time in the USA does give me the advantage of being able to concentrate on work when my US colleagues are not working.

Drawing from your extensive experiences as a Fulbright Scholar, Associate Professor, and Director of the Organizational Leadership Program, what advice would you offer to individuals aspiring to navigate the complexities of academia, cross-cultural experiences, and leadership roles simultaneously?

In short, my advice would be the following:

“Expect the unexpected and rebound if you sometimes fall.“

Things may not always go the way you want them to, but seek out “little wins” even when you may have “failed” at something (i.e. even if your paper was rejected from that coveted journal, remind yourself that you can learn from the reviewers’ comments to improve the manuscript for the next journal). Or if you mistakenly take the wrong bus, which will make you late for your next appointment, remind yourself that you cannot change the past…and then find the correct bus numbers before enjoying some of the new sights you may find on this unexpected journey.

Build a social network of people who can provide you valuable insight in a new host culture (whether it is a foreign country, or a new university/organization which you are joining just down the street of your hometown, etc.). We all have questions when we start in a new place, however, building relationships with others who have “been there, and done that” can provide a valuable source of information and answers to questions we may have, while clarifying our expectations.

Communicate. While it is not a panacea, research shows that one of the things that sound leaders do is they communicate more effectively (and/or transparently) than others.

Leadership (especially cross-cultural leadership) is challenging because it is very much about guiding others through unfamiliar, ever-changing situations that are often characterized by uncertainty among leaders and followers. More effective communication helps to reduce uncertainty by providing more information that can clarify expectations among those on the receiving end.

If you are interested in learning more about the insights shared during the conference, please visit the ID-E website.